What I Learned About Depression That No One Talks About

Depression isn’t just sadness—it’s a complex shift in how you think, feel, and function. For years, I misunderstood my own signs, mistaking fatigue for laziness and numbness for indifference. Only when I started tracking real health indicators—sleep patterns, energy levels, focus—did I see the bigger picture. This is not a cure story, but an honest look at the missteps I made while adjusting to life with depression, and what actually helped me move forward. Many people carry the weight of depression without recognizing it, not because they lack strength, but because the signs don’t always match what we expect. Understanding depression begins with unlearning myths and learning to listen to the quiet signals the body sends long before the mind raises an alarm.

The Misleading Myth of Depression

One of the most persistent barriers to recognizing depression is the myth that it looks like constant crying or overwhelming sorrow. In reality, depression often wears a far subtler mask. It may appear as emotional flatness, a lack of interest in things once enjoyed, or an unexplained heaviness in daily tasks. Many people, especially women in caregiving roles, dismiss these changes as part of aging, stress, or simply being overwhelmed. This misunderstanding delays help-seeking because the experience doesn’t feel “serious enough” to warrant attention. The truth is, depression is not defined by dramatic emotional displays but by a sustained shift in functioning across mental, physical, and behavioral domains.

Another damaging misconception is equating emotional numbness with personal weakness or laziness. When someone stops responding to loved ones, cancels plans repeatedly, or struggles to complete routine chores, they are often judged as unmotivated. But in depression, these behaviors are not choices—they are symptoms. The brain’s ability to process reward, initiate action, and regulate emotion becomes impaired. This biological reality means that willpower alone cannot reverse the condition. Recognizing this distinction is essential. It transforms self-perception from one of failure to one of physiological challenge, opening the door to compassion and appropriate care.

Equally important is understanding that depression reveals itself not only in mood but in physical and behavioral changes. Sleep disturbances, appetite shifts, slowed movement, and difficulty concentrating are often more reliable indicators than emotional state alone. These signs are measurable and observable, making them valuable tools for early detection. For many, especially those who internalize struggles, these bodily signals appear long before emotional distress becomes unbearable. By paying attention to them, individuals can intervene earlier, reducing the severity and duration of episodes. Dispelling the myth that depression is only about sadness allows for a more accurate, timely, and effective response.

Why Health Indicators Matter More Than Feelings

Feelings are subjective and often unreliable when navigating depression. What one person describes as “tired,” another might call “exhausted,” and yet another might ignore entirely. This subjectivity makes emotional self-assessment an inconsistent guide. In contrast, health indicators such as sleep duration, meal regularity, and physical activity offer objective data that can reveal patterns invisible to emotional awareness. Tracking these metrics provides a clearer picture of mental health trends over time, helping individuals recognize deterioration before it becomes critical.

Sleep, in particular, is a powerful barometer of mental well-being. Research consistently shows that both insomnia and oversleeping are strong predictors of depressive episodes. Disrupted sleep affects neurotransmitter function, impairs emotional regulation, and reduces cognitive flexibility. When someone begins sleeping significantly more or less than usual, it is not merely a side effect—it is often an early warning sign. Similarly, changes in appetite and weight, whether loss or gain, reflect underlying neurochemical shifts. These physical changes are not vanity concerns; they are biological signals that the body’s regulatory systems are under strain.

Concentration and decision-making difficulties are another set of underappreciated indicators. Struggling to follow conversations, forgetting appointments, or taking unusually long to complete simple tasks can all point to cognitive fatigue linked to depression. Unlike mood swings, which may feel fleeting or confusing, these functional impairments are concrete and measurable. When tracked consistently, they reveal trends that emotions alone cannot. For example, a person might not feel “depressed” but may notice they’ve missed three deadlines in a week or spent two hours staring at a single email. These observations provide a factual basis for action, reducing reliance on how one “thinks” they should feel.

By focusing on health indicators, individuals gain a more reliable framework for self-monitoring. This approach aligns with clinical practices, where doctors use standardized assessments that include physical and behavioral criteria, not just emotional reports. It also empowers people to take charge of their mental health without waiting for a crisis. Instead of asking, “Do I feel worse?” they can ask, “Has my sleep improved? Am I eating regularly? Am I moving my body?” These questions ground the experience in reality, making it easier to seek help when needed and celebrate progress when it occurs.

My First Big Mistake: Waiting for a Breaking Point

For years, I operated under the belief that help was only justified when I reached a breaking point—when I couldn’t get out of bed, when I burst into tears for no reason, or when someone confronted me about my state. I treated depression like a crisis that had to be proven, rather than a condition that could be managed proactively. This mindset led me to ignore early warning signs, such as increased irritability, difficulty waking up, or a growing preference for isolation. I told myself these were just phases, stress responses, or signs of being “overworked.” In reality, they were the quiet beginnings of a downward spiral.

One of the most dangerous aspects of this delay was the normalization of symptoms. Constant tiredness became my new normal. Canceling plans felt like self-care. Skipping meals was just “not being hungry.” Over time, these small changes accumulated, reshaping my daily life without my full awareness. By the time I acknowledged something was wrong, the depression had deepened, making recovery more difficult. The longer I waited, the more entrenched the patterns became—poor sleep, inactivity, social withdrawal—all reinforcing each other in a cycle that was hard to break.

Looking back, I realize that waiting for a crisis is like waiting for a fever to hit 104°F before acknowledging an infection. Early intervention is always more effective. Had I paid attention to the subtle shifts—sleeping an extra hour each night, feeling mentally foggy in the afternoons, or dreading routine tasks—I could have taken small, manageable steps to stabilize. Instead, I dismissed these signals because they didn’t match the dramatic image of depression I had in my mind. This experience taught me that the most important moments for action are often the quietest—the moments when something feels slightly off, but not alarming enough to act.

Normalizing symptoms is especially common among women who prioritize family and household responsibilities. The expectation to “keep going” makes it easy to overlook personal needs. Fatigue is attributed to parenting, irritability to hormonal changes, and disengagement to being “busy.” But when these states persist, they are not just inconveniences—they are invitations to pause and assess. Learning to recognize early signs is not a sign of weakness; it is an act of responsibility toward one’s long-term well-being. The mistake wasn’t feeling unwell—it was failing to respond when the first signs appeared.

The Trap of "Fixing" Mood with Quick Fixes

When I finally acknowledged that something was wrong, my first instinct was to fix it quickly. I tried overworking to prove I wasn’t lazy, binge-watched shows to distract myself, and relied on caffeine to push through fatigue. These strategies provided temporary relief but ultimately worsened my condition. Overworking drained my energy further, screen binges disrupted my sleep, and excessive caffeine heightened anxiety and disrupted digestion. I was treating symptoms without addressing causes, using short-term escapes that undermined long-term stability.

These quick fixes are common because they offer immediate distraction from discomfort. Scrolling through social media, eating comfort food, or taking on extra tasks can create a false sense of control. But they do not regulate the nervous system; they merely delay the need to confront underlying imbalances. In fact, many of these behaviors activate stress responses or disrupt circadian rhythms, making the body less resilient over time. For example, late-night screen use suppresses melatonin, impairing sleep quality, while emotional eating can lead to blood sugar fluctuations that affect mood stability.

The deeper issue with quick fixes is that they reinforce the idea that depression must be “fixed” rather than managed. This mindset sets unrealistic expectations—either you feel better immediately, or you’ve failed. It ignores the gradual, nonlinear nature of mental health recovery. Sustainable improvement comes not from dramatic interventions but from consistent, small adjustments that support the body’s natural rhythms. Instead of asking, “How can I feel better right now?” a more effective question is, “What can I do today to support my long-term balance?”

Replacing quick fixes with sustainable strategies requires a shift in perspective. Rather than seeking escape, the goal becomes regulation—bringing the body and mind into alignment through predictable routines. This might mean setting a consistent bedtime, stepping outside for natural light each morning, or moving the body in gentle, structured ways. These actions do not promise instant mood lifts, but they create the conditions for stability to return. Over time, they reduce reliance on temporary escapes and build a foundation for lasting well-being.

How I Started Seeing Progress—Without Realizing It

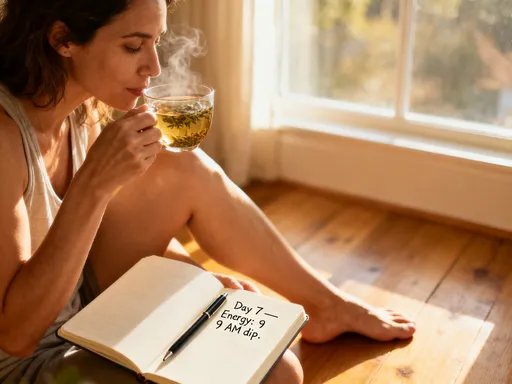

Progress in managing depression rarely announces itself with fanfare. For me, improvement came in invisible increments—sleeping 30 minutes longer without effort, preparing a meal without feeling overwhelmed, or noticing a thought like “I can do this” instead of “I can’t.” At the time, these moments felt insignificant. I didn’t recognize them as progress because they didn’t match my idea of recovery—there was no sudden joy, no dramatic turnaround. But when I began journaling and tracking daily patterns, I could see the slow accumulation of positive shifts.

Journaling became a tool for awareness. By writing down sleep times, energy levels, and small accomplishments, I created a record that emotions alone could not provide. On days when I felt stagnant, the journal showed that I had, in fact, taken a short walk, eaten three meals, or spoken kindly to myself. These entries served as evidence of forward movement, even when my internal narrative insisted otherwise. Tracking also helped me identify patterns—such as better mood on days with morning light exposure or improved focus after a consistent bedtime—allowing me to reinforce helpful behaviors.

One of the most powerful realizations was that progress is not always felt. The brain affected by depression often fails to register improvement due to negative cognitive filters. A person may be functioning better but still perceive themselves as failing. This disconnect makes external tracking essential. It provides an objective counterpoint to distorted thinking, offering a more accurate picture of reality. Over time, this practice reduced self-criticism and increased self-trust. I learned to appreciate small wins not because they erased depression, but because they represented resilience in action.

Recognizing subtle progress also changed my relationship with time. Instead of measuring recovery in weeks or months, I began to see it in daily choices. Each small act of care—a glass of water, a five-minute stretch, a moment of stillness—became a vote for stability. These choices did not eliminate depression, but they created space for it to coexist with function. Healing, I learned, is not about erasing the condition but about expanding the capacity to live well within it.

What Actually Helps: Small, Consistent Actions

What truly supported my adjustment to life with depression were not grand gestures but small, repeatable actions grounded in science. Among the most effective were light exposure, structured movement, and routine timing. Each of these interventions works not by directly altering mood but by supporting the body’s regulatory systems—circadian rhythm, neurotransmitter balance, and nervous system function. They are “body-first” strategies that indirectly create the conditions for emotional stability.

Morning light exposure, for example, helps regulate melatonin and cortisol levels, aligning the body’s internal clock with the natural day-night cycle. Just 10 to 15 minutes of natural light within an hour of waking can improve sleep quality, energy levels, and mood over time. This simple practice requires no special equipment—just stepping outside or sitting near a window. Similarly, structured movement, such as a daily walk or gentle stretching, enhances blood flow to the brain, supports neuroplasticity, and reduces inflammation. The key is consistency, not intensity. A five-minute walk done daily is more beneficial than an hour-long workout done once a week.

Establishing routine timing for meals, sleep, and activities also plays a critical role. The brain thrives on predictability. When daily rhythms are stable, the body’s stress response is less likely to activate unnecessarily. Going to bed and waking up at consistent times—even on weekends—strengthens circadian regulation, which in turn supports emotional resilience. Eating meals at regular intervals prevents blood sugar crashes that can mimic or worsen anxiety and fatigue. These routines may seem minor, but their cumulative effect is profound.

What makes these practices sustainable is their simplicity and adaptability. They do not require motivation, willpower, or dramatic lifestyle changes. They can be integrated into existing routines—walking the dog at the same time each day, opening the curtains upon waking, or setting a dinner hour. The focus is not on perfection but on repetition. Over time, these small actions build a scaffold of stability that buffers against the fluctuations of depression. They are not cures, but they are powerful tools for long-term management.

Reframing Recovery: Adjustment Over Cure

One of the most liberating shifts in my journey was letting go of the idea of “getting back to normal.” The expectation of a full return to who I was before depression created unnecessary pressure and disappointment. Instead, I began to see recovery as an ongoing process of adjustment—learning to live well with a condition that may never fully disappear. This reframing reduced shame and increased self-compassion. It allowed me to focus not on erasing depression but on building a life that accommodates it without being ruled by it.

Adjustment means accepting that healing is not linear. There will be days of progress and days of setback. The goal is not to eliminate all symptoms but to develop the awareness and tools to respond skillfully. This includes ongoing self-monitoring—continuing to track sleep, energy, and mood as part of mental health hygiene, much like brushing teeth is part of physical hygiene. It also means recognizing that help is not a one-time event but a continuous practice. Therapy, medication, lifestyle habits, and support networks are not fixes but ongoing supports.

Living with depression has taught me that resilience is not the absence of struggle but the ability to respond with awareness. It is found in the choice to step outside for light, to eat a nourishing meal, or to pause and observe without judgment. These moments, repeated over time, build a quiet strength that no crisis can erase. Healing is not about returning to who you were—it is about becoming someone who understands their limits, honors their needs, and moves forward with intention. Awareness, I’ve learned, is not just power—it is the foundation of peace.